In 1999, scientists finally put a name to one of the most devastating pandemics you’ve probably never heard of: Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd—the amphibian chytrid fungus. By the time it had a name, it had already triggered one of the largest mass extinction events in recorded biological history.

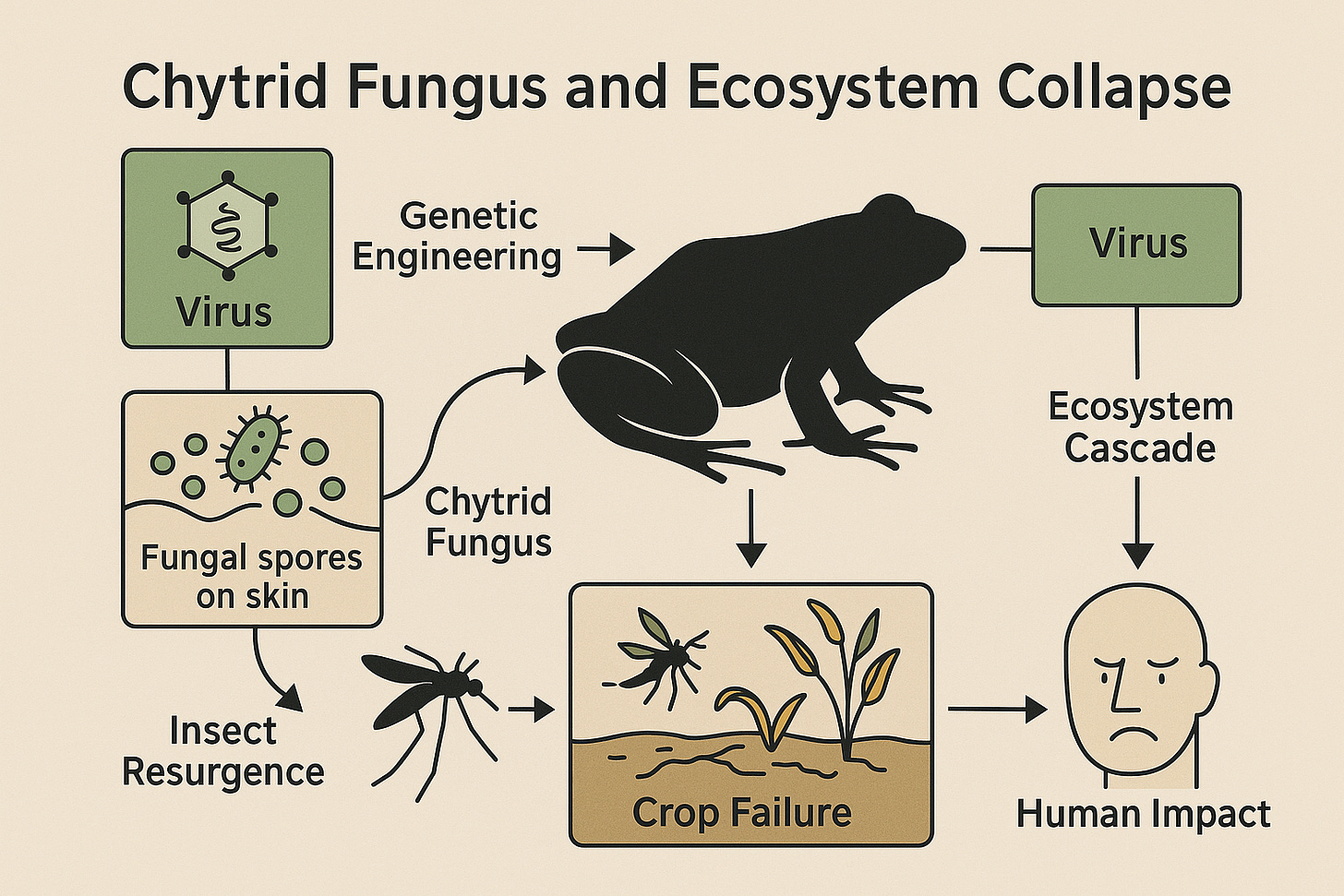

Bd has been linked to the decline or extinction of over 500 amphibian species, with at least 90 species likely wiped out entirely. And while frogs, toads, and salamanders might not be the poster children of ecosystem collapse, their disappearance sets off cascading failures that ripple through everything else. Amphibians are the keystones that hold the quiet corners of the natural world in place. When they fall, everything shifts—quietly, and then all at once.

The podcast audio was AI-generated using Google’s NotebookLM.

The Disappearing Canaries

Amphibians are more than mosquito-eaters and rainforest ambiance. They are biological barometers. Their semi-permeable skin makes them hyper-sensitive to changes in water quality, temperature, UV radiation, and environmental toxins. In short, they are nature’s early warning system.

And we are ignoring the alarm.

When frogs vanish, it’s not just a loss for biodiversity. It’s a signal that something is deeply wrong in the structure of the world. Insects surge. Crops suffer. Vector-borne diseases reemerge. Ecosystems become brittle. So when we talk about chytrid, we’re not just talking about an obscure fungal pathogen. We’re talking about the quiet unraveling of planetary resilience.

Fighting Fire with Fungus-Eating Viruses

But science, as always, is on the case. A research team at UC Riverside has discovered a virus that infects the Bd fungus itself—a single-stranded DNA virus that appears to reduce the fungus’s ability to reproduce. This discovery opens the door to a potentially groundbreaking intervention: genetically engineering the virus to suppress or destroy Bd. Nature versus nature, on our terms.

It’s a thrilling possibility. If successful, we could undo one of the greatest ecological losses of the past century. But tinkering with a virus to alter a fungus to save a frog isn’t as tidy as it sounds. Some infected strains of Bd may actually become more virulent, not less. As with many biological systems, the edges between healing and harm are thin, and often moving.

Fictional Futures, Real Warnings

This exact ambiguity—where the fix becomes the threat—is the opening premise of my debut novel, On the Wings of a Pig, which comes out this September. The story begins with the genetically engineered “solution” to chytrid backfiring catastrophically. The modified fungus mutates, spreads faster, jumps species. Ecosystems collapse. Civilization follows.

I didn’t start with frogs because they’re trendy. I started there because they are real—and they are dying. And because ecological collapse isn’t a backdrop for drama. It’s a slow-moving event that is already happening. I wanted readers to begin the story in a world that feels eerily familiar because the warning signs are already around us. They just don’t look like catastrophe yet.

This is where science fiction becomes a policy tool.

The chytrid pandemic is often treated as a niche crisis—something for ecologists in field vests with butterfly nets and notebooks. But this isn’t their issue alone. It’s mine. It’s yours. Because when we lose amphibians, we don’t just lose frogs. We lose control of the systems that make our world liveable.

If you want to read the story before you can buy the book, subscribe to the Saturday Morning Serial. One chapter, every Saturday, just for you. A thank you for supporting TCIP.

The Purpose of the Premise

I wrote On the Wings of a Pig to inspire deeper thinking about the power and peril of genetic engineering. We absolutely can solve real, meaningful global challenges when we get it right. But if our tools outpace our wisdom—if we act from hubris instead of humility—we may get it very, very wrong.

Science fiction lets us run the simulation forward. It lets us imagine unintended consequences without having to live them. The chytrid disaster in the novel is fictional, but it’s not fantastical. It’s rooted in real science and real risks. And in many ways, the novel is not a warning against science, but a rallying cry for responsible science—science that sees the whole system before reaching for a scalpel.

The reason I began the story with ecological collapse was deliberate. I wanted to bring visibility to a crisis that most people don’t see as their own. The frogs feel distant. The fungus is invisible. The threat is slow. But the consequences are real. And by the time they’re obvious, it’s already too late.

Lessons in the Living World

The scientists in the real chytrid research are moving cautiously. They’re asking the right questions. How does the virus infect the fungus? What impact does it have on virulence? Can we control it across different strains? Can it be used safely in complex, wild ecosystems? They aren’t racing toward a silver bullet. They’re studying a complex puzzle where each piece affects the whole.

We must treat ecological interventions with the same seriousness as medical ones—because the stakes are planetary health, not just patient health.

That’s the kind of science we need more of—not just in amphibian conservation, but across synthetic biology, agriculture, climate tech, and medicine. Because every engineered system touches something else. And the more powerful our tools become, the more urgent it is that we wield them with humility.

A Real World that Reads Like Fiction

We live in a time where reality increasingly sounds like science fiction. But that doesn’t mean we should surrender to techno-dystopia or utopian naivety. The truth lies somewhere in between: a future shaped by human hands, but not human ego.

So yes, frogs are dying. And yes, a virus may save them. But it’s what we choose to do next—and how we do it—that determines whether we’re writing a success story or a cautionary tale.

We’ve spent decades building tools that edit life. Now we must build the wisdom to edit wisely.

Because the wings of a pig may yet carry us to the stars. But only if we stop to look where our feet are first.

-Titus