From Secure‑by‑Design to Responsible‑by‑Design

For the last three decades, the most mature technology organizations have learned a hard lesson: security cannot be bolted on after the fact. It must be designed in—architected, tested, audited, and continuously reinforced. Secure‑by‑design did not emerge because engineers suddenly became more ethical. It emerged because complexity, scale, and interconnectedness made reactive security failures existential.

We are now at an analogous inflection point—one that extends beyond cybersecurity and into the fabric of innovation itself.

The technologies defining this era—artificial intelligence, advanced biotechnology, robotics, fusion and new energy systems, and novel computing paradigms—do not merely add new capabilities. They reconfigure power, agency, labor, geopolitics, and responsibility itself. They are not tools that sit neatly inside existing institutions; they stress those institutions, bypass them, and sometimes render them obsolete.

In this context, responsibility can no longer be treated as a moral aspiration or a compliance checklist. Just as security matured into an engineering discipline, responsibility must now do the same.

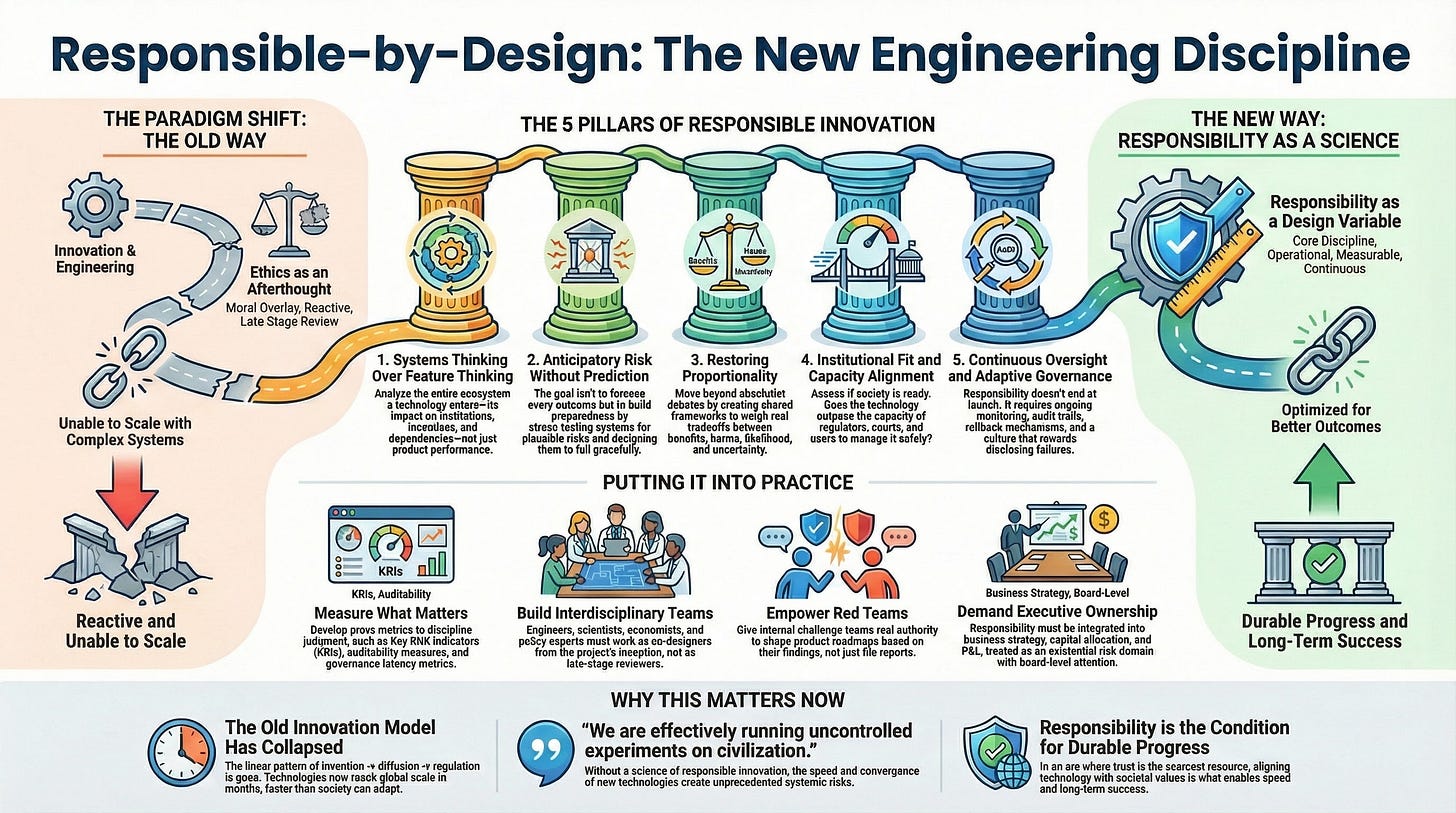

We need a responsible‑by‑design paradigm—one that is as rigorous, operational, and measurable as secure‑by‑design ever became.

This is the animating premise of The Science of Responsible Innovation.

In 2026, we are past the novelty phase of generative AI and well into the deployment‑and‑consequences phase. Similar transitions are unfolding across biotechnology, robotics, and energy. The central question is no longer whether we can build these systems, but whether we can govern their creation and deployment without destabilizing the societies they are meant to serve.

I want to lay out how TCIP will think, write, convene, and build in 2026—and why the next era of progress depends on treating responsibility not as an ethical afterthought, but as a scientific discipline.

The podcast audio was AI-generated using Google’s NotebookLM.

Part I: From Ethics to Engineering Responsibility

Why Ethics Alone No Longer Scales

Ethics has played an essential role in shaping modern technology discourse. It gives us language for values—fairness, dignity, autonomy, beneficence. It provides moral guardrails and helps articulate what should not be done.

But ethics, on its own, does not scale to systems of this magnitude.

Ethical frameworks are necessarily abstract. They are interpretive rather than prescriptive. They tell us what we value, but rarely tell us how to engineer tradeoffs under real constraints: incomplete data, conflicting objectives, adversarial environments, and non‑negotiable timelines.

Telling a product team to “avoid bias” does not specify which dataset to discard when representativeness conflicts with accuracy. Telling a research lab to “consider societal impact” does not explain how to weigh lives saved today against uncertain risks decades from now. In practice, ethics too often becomes a late‑stage review process—arriving after architectures are fixed and incentives locked in.

At that point, ethics becomes reactive. Harm mitigation replaces harm prevention.

Responsibility as a Design Constraint

A science of responsible innovation begins from a different premise: responsibility is not a moral overlay, but a design variable.

To call responsibility a science is to make three specific claims:

First, responsibility can be operationalized. It can be translated into concrete requirements, metrics, and processes that shape technical and organizational decisions.

Second, responsibility can be optimized. There are better and worse ways to align technological capability with human values, institutional capacity, and societal readiness.

Third, responsibility evolves. As systems interact with the real world, their risks, benefits, and failure modes change. Responsible innovation therefore requires continuous measurement, feedback, and adaptation.

This reframing moves responsibility out of philosophy seminars and into engineering reviews, product roadmaps, capital allocation decisions, and board‑level governance.

Part II: The Core Pillars of a Science of Responsible Innovation

1. Systems Thinking Over Feature Thinking

Most technological harm does not arise from malicious intent. It arises from systems—feedback loops, emergent behaviors, misaligned incentives, and second‑ or third‑order effects that were invisible at the point of design.

A science of responsible innovation therefore begins with systems thinking. It asks:

What ecosystems will this technology enter?

What institutions will it stress, bypass, or hollow out?

What incentives will it amplify or distort?

What dependencies will it create—and how reversible are they?

This requires moving beyond product‑centric thinking toward full lifecycle analysis. In AI, this means examining data provenance, labor practices, deployment contexts, and governance interfaces—not just model performance. In biotechnology, it means considering supply chains, regulatory regimes, and dual‑use risks alongside molecular function.

Systems thinking does not slow innovation. It prevents brittle success—products that scale rapidly only to collapse under the weight of their own externalities.

2. Anticipatory Risk Without the Illusion of Omniscience

A common critique of responsible innovation is that it demands impossible foresight. How can we predict every misuse, every unintended consequence, every societal reaction?

The answer is: we cannot—and we do not need to.

A science of responsible innovation does not seek prediction; it seeks preparedness. It focuses on identifying plausible risk surfaces, stress‑testing assumptions, and building adaptive capacity.

This is where techniques such as scenario analysis, violet teaming, and horizon scanning become central. Rather than asking “What will happen?”, we ask:

What could go wrong under reasonable assumptions?

What happens if this system is used at scale, under adversarial pressure, or outside its intended context?

Where are the irreversibilities?

Responsibility, in this sense, is less about foreseeing the future and more about designing systems that fail gracefully—and visibly—when the future surprises us.

3. The Collapse of Proportionality

One of the most damaging pathologies of contemporary technology discourse is the collapse of proportionality.

Every risk is framed as catastrophic. Every acceleration is framed as reckless. Every delay is framed as negligent.

When proportionality collapses, decision‑making collapses with it. Leaders oscillate between paralysis and overreach. Public debate becomes absolutist. Tradeoffs—real, unavoidable tradeoffs—are treated as moral failures rather than engineering realities.

A science of responsible innovation restores proportionality. It creates shared frameworks for reasoning about magnitude, likelihood, reversibility, and distribution of harm and benefit.

This includes weighing immediate life-saving benefits against high-uncertainty, high-severity future risks; democratizing access against increasing misuse potential; and decentralization against accountability.

Responsible innovation does not deny these tensions. It makes them explicit, measurable, and governable.

4. Institutional Fit and Capacity Alignment

Technologies do not land in abstract societies. They land in institutions—with laws, norms, competencies, and failure modes.

Responsible innovation therefore asks not only “Is this technology safe?” but “Is this system ready?”

Do regulators have the technical capacity to oversee it?

Do courts have frameworks to adjudicate harm?

Do users understand its limits?

In some cases, responsibility means delaying deployment until institutional capacity catches up. In others, it means investing directly in that capacity as part of the innovation process.

The lesson of secure‑by‑design applies here: technology that outruns governance does not remain free—it invites overcorrection.

5. Continuous Oversight and Adaptive Governance

Responsibility does not end at launch.

Complex systems evolve. Users adapt. Adversaries probe. Markets shift. Responsible innovation therefore treats governance as continuous, not episodic.

This includes post‑deployment monitoring, incident reporting, audit trails, rollback mechanisms, and sunset clauses. It also requires cultural norms that reward early disclosure of failure rather than concealment.

Responsibility, like security, is never “done.” It is maintained.

Part III: Measurement—Turning Responsibility Into a Science

If responsibility is a science, it must be measurable.

This does not mean reducing ethics to a single number. It means developing proxy metrics that allow organizations to reason rigorously about risk, benefit, and uncertainty.

Examples include:

Key Risk Indicators (KRIs) tied to misuse likelihood, systemic dependency, or institutional fragility.

Economic models that quantify near‑term benefits against long‑tail downside.

Auditability measures that track decision provenance and model evolution.

Governance latency metrics that assess how quickly oversight mechanisms can respond to failure.

Measurement does not eliminate judgment—but it disciplines it. It allows disagreements to be surfaced, assumptions to be tested, and learning to compound over time.

Part IV: Practicing Responsible‑by‑Design

What does this science look like in practice?

It looks like interdisciplinary teams where engineers, domain scientists, economists, and policy experts work together from inception—not as reviewers, but as co‑designers.

It looks like violet teams with real authority, whose findings shape roadmaps rather than decorate reports.

It looks like staged deployment strategies that deliberately constrain early use cases and expand only as evidence accumulates.

Crucially, it looks like executive ownership.

A science of responsible innovation cannot live in a safety silo. It must be integrated into business strategy, capital allocation, and P&L accountability. Leaders must treat responsibility the way they now treat cybersecurity or financial controls: as an existential risk domain that demands board‑level attention.

This is where responsible‑by‑design becomes real.

Part V: Why This Matters Now

For most of the industrial era, innovation followed a linear pattern: invention, diffusion, regulation. Society had time to adapt between phases.

That model has collapsed.

Foundation models now reach global scale in months. Biological techniques propagate faster than regulatory consensus. Autonomous systems interact at machine speed.

Without a science of responsible innovation, we are effectively running uncontrolled experiments on civilization.

Convergence amplifies both reward and risk. Trust becomes the scarce resource. And paradoxically, speed increasingly depends on alignment rather than recklessness.

Responsibility is not the opposite of progress. It is the condition for durable progress.

The TCIP Roadmap for 2026

Over the next year, TCIP will focus on building and articulating this science—through essays, frameworks, case studies, and convenings that translate responsible‑by‑design from abstraction into practice.

This is why the Science of Responsible Innovation will be the central theme of TCIP in 2026.

At the frontier of technology, humanity is the experiment. This science is how we ensure that experiment is worth running.

Happy New Year,

-Titus